Violence

The First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution generally prevents the government from restricting the creation or viewing of art on the Internet that contains violent material. Violent imagery has been a part of great works of art and literature for thousands of years and U.S. courts recognize this, deciding in a range of cases that laws that try to restrict violence in art and the media are unconstitutional.

But in recent years there has been much debate about violence and its possible effects on children, mainly in the context of video games. Some groups and government officials have called for limiting children’s access to violence in video games, on television, and on the Internet. Although parents can easily control what media and Internet content their children have access to by using filtering software, voluntary ratings systems, and devices such as digital video recorders, some people still think “there ought to be a law” that controls when and where violent content can be displayed.

This area of law is likely to be the focus of continued debate, so if you have images of violence in your art, be aware that the laws might change and that it’s important to stay aware of new developments in Congress, state legislatures, and the courts. Also, regardless of whether your art depicts violent images or sounds, if it directly encourages others to be violent, you could find yourself in legal trouble. See our discussion of fighting words and incitement to violence for more.

The Basics

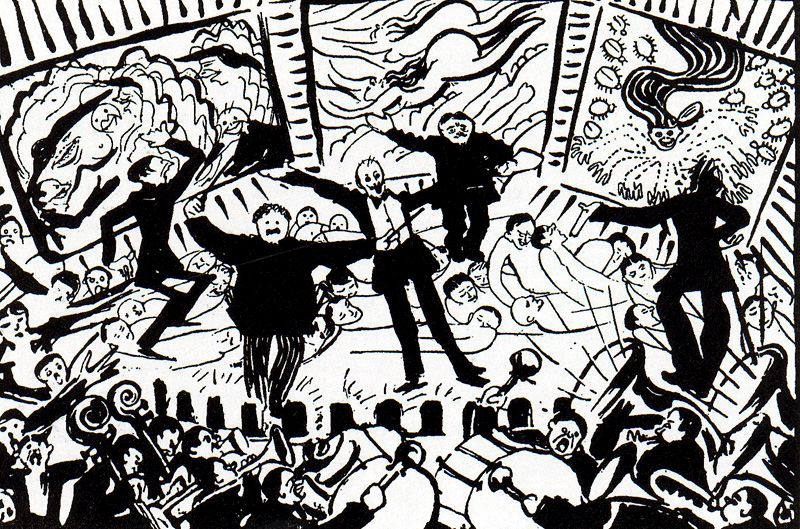

Umberto Boccioni – A Futurist Evening in Milan, 1915

Violent imagery has a long tradition in art, and is generally shielded from government censorship. However, the government may be able to regulate violent sexual content or art that encourages violence, regardless of whether the art actually depicts violence.

In recent years, legislators have frequently targeted violent video games for regulation. So far, all of the laws that have aimed to limit kids’ ability to access violent games have been ruled to violate the Constitution, but this is still a frequent subject of legislation and litigation.

If your art includes violent content, be aware that the current strong First Amendment right you have to create and disseminate violent content continues to be challenged. You should also keep in mind that the terms of service of the website or server that hosts your material can prohibit you from posting violent content.

Violent Sexual Content

One of the few instances where the government can regulate or penalize violent content without violating the First Amendment is if it contains sexual material that is deemed to be “obscene.” (See our pages on sexual content for a discussion of the legal definition of “obscene.”) If violence is displayed together with very explicit sexual images, a judge might consider the work as a whole to be obscene, and therefore illegal. While the government can ban obscenity outright, the standards for finding content to be obscene are high, and most mainstream art won’t fall into this category even if it contains what some people would consider pornographic content.

Violent Video Games

The video gaming industry has recently faced frequent attempts by the government to censor violent content. A number of states and cities have passed laws to limit children’s access to violent video games, but judges have thus far decided that these laws violate the First Amendment and so are not enforceable. A case is pending in 2010 in the U.S. Supreme Court on this issue, and thus there is some chance the law concerning violent content could change.

The ratings that are used to categorize video games (as well as television shows and movies) as appropriate for children, teenagers, or adults are all a result of voluntary efforts by the industry to enable their customers to make more informed media choices. The government can’t require companies or individuals to label their work as containing particular content, especially content deemed problematic by the government. Such “compelled speech” also violates the First Amendment.

Terms of Service

Because the First Amendment only prohibits the government from censoring or regulating violent speech, an artist is more likely to run into restrictions developed by private entities such as website operators and web hosting companies. Many major Internet service companies maintain websites that permit users to post content or provide server space for individuals to run their own websites. These services often have rules against using their services to post “graphic or gratuitous” violent imagery, and they may take down content that violates their rules. These private companies are within their rights to do this, and it is important for you to understand a sites terms of service, so that you know what can be posted and what the risk is that art with violent imagery might be taken down. For more information, read our discussion of Terms of Service Violations.

Inciting Violence

Under the First Amendment, art that directly incites or encourages others to be violent can be restricted or penalized. Regardless of whether your art depicts violent images or sounds, if it strongly encourages others to be violent toward specific individuals at a certain time and place, it could be deemed to be illegal. The standards for “threatening” speech are fairly high: there has to be a true threat of violence where the work is aimed at encouraging specific violent acts in the very near future, especially against particular individuals or groups of people. General encouragement of violence (even in in the context, for example, of urging overthowing a government) is usually not enough to be considered a true threat, and should be protected.

The First Amendment provides strong protection against government attempts to censor violent art, so the chances that you’ll run into legal trouble are low. But there are still some things you should be aware of, and this section includes some practical tips on how to avoid legal trouble, as well as some pointers on how to make the way you display your violent art more user-friendly if you’re concerned about fielding complaints from people who don’t like your art.

Violence in art is permissible under the First Amendment.

The government can’t forbid violent content, and can only control it in very limited ways. In general, if your art is just graphically violent with no sexual content, you're not likely to face legal challenges to your work.

That said, if you want to avoid conflict over potentially controversial work, you might consider putting particularly graphic material behind a warning to users that some viewers might find your work disturbing. This is a relatively simple way to avoid complaints, either directed to you as the artist or to the service provider hosting your material, since those viewers who might be offended by your work can choose not to click through.

Violent sexual content might be considered legally obscene.

Obscenity is generally illegal under both federal and state law. The government can prosecute you for posting obscene violent material, though it takes a judge and jury to decide if your art is obscene. There must be some sexual component to a work for it to be considered obscene.

No website, server, or ISP has to host your content for you.

Read the terms of service before you post so that you know what is and is not allowed (if they’re paying attention or receive complaints).

Art that encourages or threatens specific acts of violence can be illegal.

The threat, however, has to be fairly specific, directed at a certain person or group of people, and likely to happen soon.

The General Rule

Winters v. New York, 333 U.S. 507 (1948)

This Supreme Court case struck down a New York state law that would have made it a crime to print, publish, or sell any publication “principally made up of criminal news, police reports, or accounts of criminal deeds, or pictures, or stories of deeds of bloodshed, lust, or crime.” The publication at issue was a magazine called “Headquarters Detective: True Cases from the Police Blotter, June 1940.”

The Court held that this law was too vague to inform people of exactly what was or wasn’t prohibited, and thus constituted an unconstitutional restriction on the individual’s fundamental right to free expression. The Court noted, “Though we can see nothing of any possible value to society in these magazines, they are as much entitled to the protection of free speech as the best of literature.”

Video Software Dealers Association v. Webster, 968 F.2d 684 (8th Cir. 1992)

The federal Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals struck down a Missouri state law that prohibited stores from renting or selling video cassettes to minors (under the age of seventeen) if those videos “ha[d] a tendency to cater or appeal to morbid interests in violence for persons under the age of seventeen; and depict[ed] violence in a way which is patently offensive to the average person applying contemporary adult community standards with respect to what is suitable for persons under the age of seventeen.”

The court determined that this law was not narrowly tailored enough to meet the state’s interest in protecting minors from extremely violent content without infringing on the right to free expression. The statute was vague and did not adequately define what was meant by “violence.” The criteria the statute outlined for what material fell under its regulation were similar to the components of the obscenity definition, but the court noted that “material that contains violence but not depictions or descriptions of sexual conduct cannot be obscene,” and so “videos depicting only violence do not fall within the legal definition of obscenity for either minors or adults.”

United States v. Stevens, 559 U.S. ____ (2010)

In this case, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down a federal statute that prohibited depictions of animal cruelty, finding that the statute’s scope was too broad and encompassed a significant amount of speech protected by the First Amendment. The problem with the law was that it forbid depictions of animals cruelty. The government has long had the power to prohibit actual cruelty to animals, but by targeting depictions of cruelty, the challenged statute covered images and video used not to commit but to talk about animal cruelty. And, because the statute included in its definition of “cruel” conduct instances when an animal was wounded or killed, the law prohibited everything from television shows about hunting, to exposés about animals’ living conditions on factory farms, to videos of dog fighting and the “crush” videos the statute was originally drafted to target. Because of the vast amount of constitutionally protected speech this law would have prohibited, the Supreme Court invalidated it as a violation of the First Amendment.

Violence and Video Games

There is currently a vigorous debate about the effect of media violence on children. Academics, parents, government officials, and ordinary people often argue that exposure to violent content, whether frequent or more limited, is damaging to children. People blame violent video games, television shows, and websites for an increase in violence in schools and among teenagers. In examining the social-science research on exposure to violent media and violent behavior in minors, federal courts have generally concluded that there is little evidence of a link between the two. (See, e.g., Schwarzenegger v. Entertainment Merchants Association, below.)

Federal agencies have also examined the effects of media violence on children, and have released their own reports on the issue. In 2007, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), which has legal authority to regulate television content, released a report concluding “that exposure to violence in the media can increase aggressive behavior in children, at least in the short term.” The report also calls on Congress to pass a law that would allow the FCC to restrict violent content on television. But, based on the current cases, a move by Congress or the FCC to regulate violence would likely violate the First Amendment.

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) also released a report in 2007, which focused specifically on the marketing of violent content to children, and included a number of recommendations to the various industries for how to improve the clarity and consistency of their voluntary ratings. The FTC continued to support the industries’ efforts to address the problem on their own, rather than having Congress dictate a course of action.

Numerous states and localities have sought to regulate violent video games, but those laws have to date always been held to be unconstitutional. A few of the cases are described below, including one current (2010) case that is on appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.

American Amusement Machines v. Kendrick, 244 F. 3d 572 (7th Cir. 2001)

The federal Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals struck down an Indiana state law that prohibited arcade operators from allowing an unaccompanied minor to access video games that were deemed “harmful to minors” because of their violent or sexual content. In this case, the Court held that video games are a form of speech, and that the state hadn’t demonstrated that any solid benefit would actually be gained from this regulation. As Judge Posner noted, “Classic literature and art . . . are saturated with graphic scenes of violence, whether narrated or pictorial” – there is no tradition of regulating depictions of violence in the United States, and video games enjoy the same protection under the First Amendment as any other form of speech. The regulation would be a burden on free speech and harm the individual’s right to free expression. Thus, the balance tipped heavily in favor of free expression, and the law was declared unconstitutional.

Interactive Digital Software Association v. St. Louis County, Missouri, 329 F. 3d 954 (8th Cir. 2003)

The federal Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals struck down a Missouri law that prohibited selling or renting violent video games to minors, or permitting them to play such games, without parental consent. The court held that “that violent video games are as much entitled to the protection of free speech as the best of literature.” The fact that video games are a new and interactive medium does not change the fact that they are a medium of expression entitled to full First Amendment protection.

The challenged ordinance attempted to regulate speech based on its content, but the state failed to demonstrate that the law actually supported a compelling state interest. The court held that “the government may not simply surmise that an ordinance is serving a compelling state interest because society in general believes that continued exposure to violence can be harmful to children. Where First-Amendment rights are at stake, the government must present more than anecdote and supposition” to support such legislation. The court also held that “[t]he government cannot silence protected speech by wrapping itself in the cloak of parental authority,” and that it was not the appropriate role of the government to enact legislation with the aim of parenting people’s children for them, particularly when people’s First-Amendment rights are at stake. This case is an excellent example of just how strongly the right to free speech is protected in the United States.

Schwarzenegger v. Entertainment Merchants Association, 556 F.3d 950

(9th Cir. 2009), cert. granted, 559 S. Ct. 1448 (2010)

In a move that was suprising to many observers, the Supreme Court has decided to review California's mandatory video game–labeling statute in the Court's upcoming 2010-2011 term. In 2009, the federal Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals struck down the state law that would require the labeling of violent video games and would prohibit their rental or sale to minors. As in the above cases, the court concluded that this law is unconstitutional, in part because the state did not establish a strong enough relationship between their asserted interest in protecting minors from harm and the effects of the speech-restrictive regulation.

The Supreme Court's decision to review this case is an unusual move – the Court generally takes a case to resolve a split in opinion between the circuits, but every district and circuit court to review similar statutes has struck them down as violating the First Amendment. The Court will be reviewing two questions in this case. The first is whether the First Amendment prohibits the government from barring the sale of violent video games to minors; to date, violent content has received full First Amendment protection, and a carve-out of a new category of unprotected speech would be a seismic shift in the law. If the government can restrict minors’ access to games with violent aspects, it’s hard to imagine that restrictions on books, movies, and other art could be far behind. The second question is whether, if the government could permissibly regulate minors’ access to violent content, it would be required to establish a direct causal link between exposure to violent video games and physical or psychological harm to minors. This question forms the heart of the debate surrounding minors and violent games, and the Court’s decision will have a significant impact on free speech and creative expression.

Incitement to Violence

Sheehan v. Gregoire, 272 F. Supp. 2d 1135 (W.D. Wash. 2003)

The District Court for the Western District of Washington struck down a state law that prohibited the publication of law enforcement officials’ personal information “with the intent to harm or intimidate.” This personal information was already available to the public, published by the government. The court found that the statute was a content-based restriction on speech with no reference to objective standards of harm. States can’t regulate someone’s speech on the basis of an inferred intent to harm when the actual material published, in this case, names and phone numbers, contains no actual threat.